Are LOLCats Making Us Smart?

Academics are starting to take a hard look at Internet memes and the cultural sensibilities they reflect.

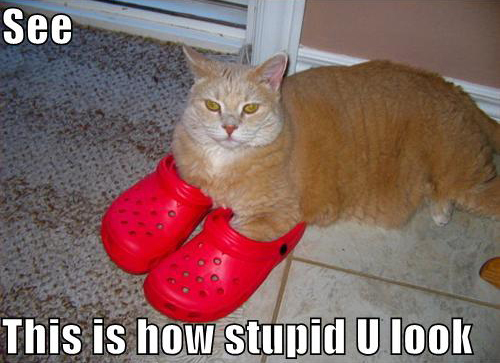

What could possibly be said of LOLCats that is of any consequence at all? After all, LOLCats are nothing but pictures of cats with silly captions that defy conventional rules of spelling and grammar. What do they matter?

They don't. Or at least, the content -- the "what" -- of LOLCats doesn't much matter. But the why of LOLCats has proved to be rich terrain for Kate Miltner who received her Master's Degree from the London School of Economics for her dissertation on the appeal of LOLCats (pdf) and spoke at ROFLCon -- a conference devoted to Internet memes and the mini-celebrities that have emerged -- on a panel called "Adventures in Aca-meme-ia" this past weekend at MIT. (A video by my colleague Kasia Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg, "Memes Are People Too," explores the events of ROFLCon in greater detail.)

Why, Miltner asks, have these cat pictures become the cultural phenomenon that they are? "LOLCats," she writes, "have spawned two best-selling books, a Bible translation, an art show, and an off-Broadway musical. LOLCats have also inspired the development of a massive international community; in July 2011, thousands of Cheezburger devotees [the central LOLCats hub on the web] converged upon Safeco Field in Seattle for Cheezburger Field Day." What is it about these little kitties that speaks to people?

According to Miltner, "When it came to LOLCats, sharing and creating were often different means to the same end: making meaningful connections with others." At their core LOLCats weren't about those funny captions, the weird grammar, or the cute kitties, but people employed those qualities in service of that primary goal of human connection.

Miltner found that LOLCats consumers tended to fall into one of three groups. The groups had different cultures and attitudes, but for all three LOLCats provided a platform for communication and connection. The first group, which Miltner labeled "Cheezfrenz," was made up of LOLCats diehards. "They are invested LOLCat lovers whose interest in LOLCats generally stems from their affinity for cats," she explains. They tended to be involved in I Can Haz Cheezburger, the website of the LOLCat-loving community. Miltner found that for these women (and they were all women in her sample), the ICHC community appealed because it was, in the words of one "Cheezfrend" "a place to be safe and kind" for people who "want to be nice, want to be happy, want to give support, want to smile." Cheezfrenz recognized and bonded with each other (i.e. formed an in-group, in sociology-speak) by their correct use of LOLspeak (the grammar and spelling of LOLCats).

The second group, which Miltner calls the MemeGeeks (many of whom, she noted, make up ROFLCon's devoted base), uses different tactics for discerning in- and out-group boundaries, but the effect is the same: connection with your group. For the predominantly male MemeGeeks, they established their affiliation with the group by making LOLCats that refer to more obscure memes -- the more obscure, the better. They don't seek out LOLCats, but they play around with them on Reddit and Tumblr. The final group were the casual users, made up of people who are bored at work and who share LOLCats they find funny and cute. They were split pretty evenly male-female. For them, they emailed and Facebook-shared cats not with people they knew from the Internet but close friends and family -- it was a way of staying in touch and sharing a laugh during a day at the office.

While the specifics of Miltner's analysis may uniquely describe LOLCats, the argument she is making is bigger: Like space-invasion films of the mid-20th century or soap operas of more recent decades, the cultural phenomena of Internet memes reflect societal anxieties or desires, and that through studying these memes we can better understand what is going on in the collective mind of our culture. To ignore Internet memes, is to ignore the huge outpouring of modern folk culture that is occurring online, and -- taking the analysis one step further yet -- the ways that the Internet's particular participatory capacity is shaping that culture.

For LOLCats, that cultural reflection shows us a society that finds humor in anthropomorphized cats, and that builds connections by sharing the resulting laughs with other people. Other memes work in similar ways: People find something funny and they share it. It is the question of what we find funny that let's us see into our culture. And, unsurprisingly, this can have a darker side: Meme-humor, just like offline humor, sometimes reflects back at us the racism, sexism, and other prejudices that have deep roots in society.

This was perhaps most apparent at ROFLCon in a discussion of the memes that have shot around Brazil, a country known for its extreme income inequality and persistently high illiteracy rate. This video, embedded below, features a likely illiterate woman who has clearly never heard of the letter "w" (not a common letter in Portuguese, it should be noted), and cannot get the URL of YouTube straight, something apparently funny to the Brazilian YouTube-watching population.

Of course, mocking poor people is not a uniquely Brazilian phenomenon. It's hard not to see the same elements at work in last summer's craze begun by a local TV-station interview of the brother of a woman who had nearly been raped in her own home. In the video, Antoine Dodson implores viewers to "hide your kids, hide your wife, and hide your husband" because there's a rapist out there. His words were remixed into songs, and covered by rock bands, punk bands, and even a marching band.

But were people laughing with Dodson or at Dodson? Well, he wasn't laughing, so that kind of answers the question. (Also, one look at the comments on YouTube will give you a good taste of the racist reactions to the video.) As Baratunde Thurston explained to NPR:

As the remix took off, I became increasingly uncomfortable with its separation from the underlying situation. A woman was sexually assaulted and her brother was rightfully upset. People online seemed to be laughing at him and not with him (because he wasn't laughing), as Dodson fulfilled multiple stereotypes in one short news segment. Watching the wider Web jump on this meme, all but forgetting why Dodson was upset, seemed like a form of 'class tourism.' Folks with no exposure to the projects could dip their toes into YouTube and get a taste.

That said, it should be noted that voyeurism on the part of the audience aside, Dodson was there at ROFLCon, basking in his fame, as he has done happily since the video went viral. People may have been laughing at him, but he has joined right in the fun, and benefited from some serious business and reputation-management savvy. Does Dodson's pleasure in his accidental fame and his subsequent success mitigate the classism and racism that at least in part fueled the meme's popularity? I am still working through that and hope to have an answer for you in the next several decades.

Another viral phenomenon from earlier this year also drew energy from the demographic cleavages that cut across our society, but it did so in ways quite different from the Antoine Dodson meme, and that was the "Shit Girls Say" video and its hundreds upon hundreds of spin-offs, including the very popular "Shit White Girls Say to Black Girls," which put a sharp point on the subtly racist comments that get tossed off every day.

Racialicious's Latoya Peterson, who spoke on ROFLCon's LOLitics panel, described the "shit people say" sensation as both "problematic and subversive." Even though the meme trafficked in problematic stereotypes, it also allowed people to explore questions of identity and to offer, humorously, their own social commentary on what they saw. In this way, the participatory nature of the meme, and the Internet more broadly, gave space for people to have a voice in discussion of race and class and sexual orientation that weren't possible when media was more centralized.

Conversations like these coursed through this year's ROFLCon, which displayed its serious side not just on the "aca-meme-ia" and LOLitics panels but also in discussions among activists talking about the fight for a free Internet and a keynote from Harvard law professor Jonathan Zittrain speaking about the way memes can transcend the cynicism we have about public life. But the weekend was full of lulz too, for sure. You put Chuck Testa or Double Rainbow Guy on a panel and lulz are more or less guaranteed. The message, all together, was loud and clear: Lulz can offer us a bit of salvation from our broken civic life. Because sometimes, if you don't lol, you'll cry.