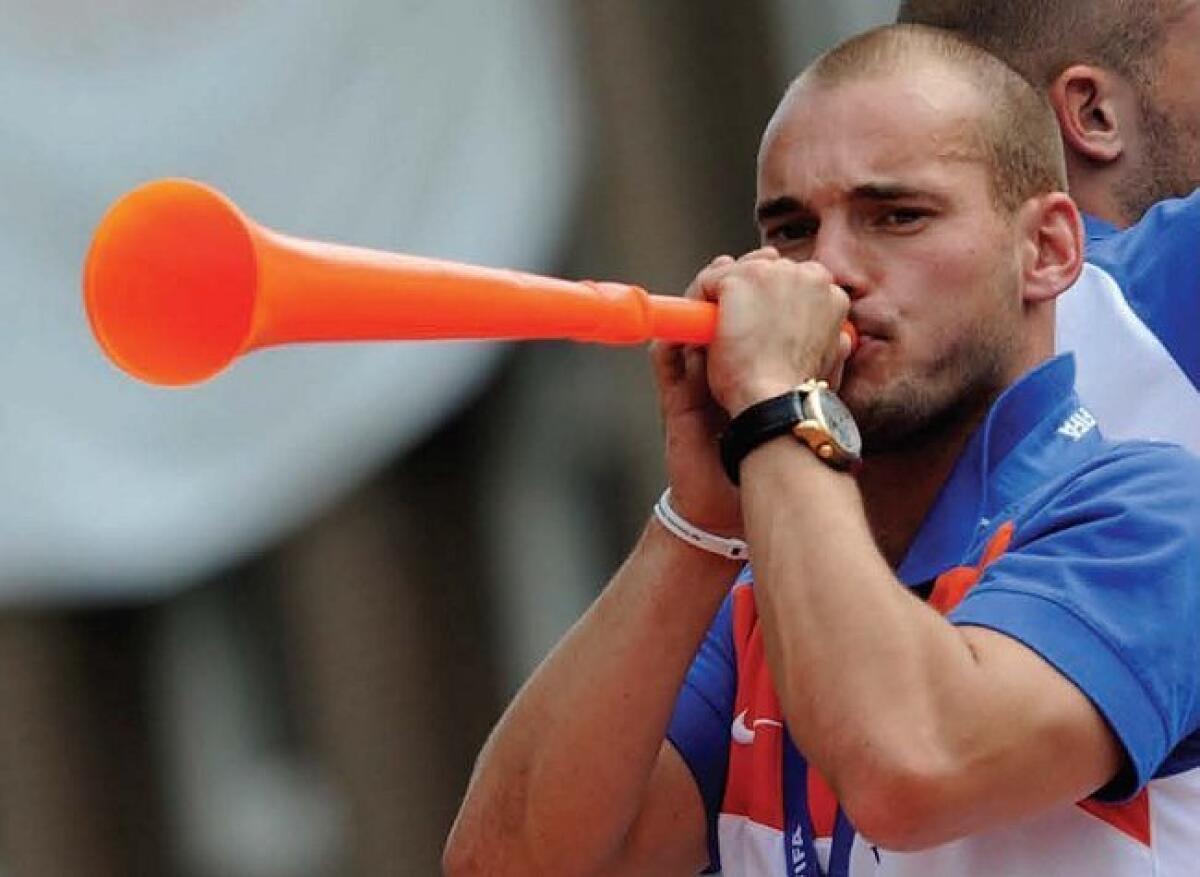

Plans for vuvuzela night blown out of stadium

Steve Schnall, San Diego State’s associate athletic director for marketing, watched soccer’s World Cup this summer on TV and heard the incessant buzzing from the long, loud plastic air horns that South Africans call vuvuzelas. And started scheming.

A giveaway night at Qualcomm Stadium for an Aztecs football game. Red and black horns adorned with a sponsor’s logo. Distributed to the first 10,000, maybe 15,000, people through the gates. With everyone blowing them in unison as the opposing quarterback tries to bark signals in the fourth quarter.

Delay of game penalties … false start penalties … receivers running the wrong routes … linemen missing blocks … general chaos amid the infernal bleating …

It won’t happen.

It won’t, because Mountain West Conference Associate Commissioner Dan Butterly was watching the World Cup, too, and thinking the same thing. Said Butterly, “I instantly thought, ‘I’m waiting for the first institution to call me saying they have a sponsor that wants to give away these horns.’”

Waiting to cite bylaw 1.5 in the conference handbook:

Artificial noisemakers are prohibited during athletic competition in all sports at all times; this includes non-conference as well as conference competition. An institution shall not distribute or cause to be distributed artificial noisemakers.

It won’t happen at Chargers games, either, and probably not at the Padres. A variety of other teams and leagues have outlawed them as well, including several English Premier League soccer clubs.

The NFL has a long-standing ban of “noisemakers of any kind” and mandates that “items of this nature should be confiscated by stadium security.” Major League Baseball has no such blanket rule, but official customer guidelines for Petco Park prohibit “musical instruments or any type of noisemaking device.”

That doesn’t mean the earsplitting drone of vuvuzelas has not echoed through Qualcomm Stadium and Petco Park. They have.

Both have hosted the Mexican national soccer team in its regular visits to San Diego, and organizers have amended any applicable policies to allow the colorful horns — “cornetas” in Spanish — that have been part of Mexican soccer lore for decades. They even hawk them in the concourse for as little as $5.

“They’re our best-selling concession item, by miles,” said La Mesa resident Paul Mendes, a soccer promoter who has managed hundreds of games across the United States. “On a typical night, we’ll sell 3,000 to 5,000.”

And that was before the vuvuzela’s profile was so audibly elevated at the 2010 World Cup. That relentless buzzing you heard through your TV set (even, seemingly, when the mute button was on) was probably the work of 5,000 horns scattered through a crowd of 50,000 in an open-air facility.

Imagine two or three times as many in a domed stadium in the fourth quarter of a football game, or an indoor arena.

Or put it this way: A subway emits about 90 decibels of sound, a lawn mower about 95 or 100, a power saw about 110. The ear’s pain threshold is about 125.

A single vuvuzela blown properly, according to a report published in the South Africa Medical Journal this year, unleashes between 113 and 131 decibels of wailing fury depending if your ear is 6 feet away or the guy blowing it is in the seat directly behind you.

(Which might explain why ear plugs were the next hottest-selling item outside stadiums in South Africa.)

“In soccer, you’re never really reacting to commands,” Mendes said. “It’s a free-flowing game. The only impact of the noise would be if you can’t hear the referee’s whistle, but linesmen in soccer have flags so it’s visual. It doesn’t impact the course of play.

“In other sports, it does.”

Ask the Florida Marlins. They held a vuvuzela night during the World Cup and handed out 15,000 smaller horns (about half the size of the two-foot South African version). The fans seemed to like it. The marketing and ticketing departments seemed to like it. The players and managers hated it.

In the ensuing din, home plate umpire Lance Barksdale apparently misunderstand a lineup change by manager Fredi Gonzalez — costing the Marlins a leadoff walk in a 5-5 game in the ninth inning because a player batted out of order. The Marlins ultimately lost 9-8 in 11 innings; four days later, Gonzalez was fired.

“The worst handout or giveaway I’ve ever been a part of in baseball,” Marlins second baseman Dan Uggla called it.

A clause in the Petco Park regulations allows the Padres to waive the noisemaker ban, but club officials say there are no imminent plans to do it.

And it doesn’t sound like Butterly or the Mountain West Conference will budge anytime soon, or the Aztecs are preparing to challenge them. A first offense of rule 1.5 is a warning from the conference office. A second offense carries a fine.

Butterly was at a conference basketball game last season and heard the distinctive bleating that meant one of two things: Someone had smuggled in a goat, or a vuvuzela.

He triangulated its location and had it confiscated (the vuvuzela, not a goat).

“I’m not saying they’re a bad idea,” SDSU’s Schnall said. “I’m just saying they violate our conference rules.”

Don’t plan on seeing, or hearing, them at the Aug. 1 Ultimate Fighting Championship event in the San Diego Sports Arena, either.

“This decision was pretty simple,” UFC President Dana White recently explained in banning the horns. “Vuvuzelas make the most horrific sound I’ve ever heard. I’d rather let Brock (Lesnar) punch me in the face than hear 15,000 people blow on those things.”