Boston Globe Magazine (cover story)

One cold April night in 1983, authorities from the Drug Enforcement Administration and Maine State Police arrived at the Northeast Harbor Marina on Mount Desert Island. With them, a drug-sniffing dog strained at the end of a leash. They’d received an anonymous tip that some of the scallop boats tied up at the dock had been carrying illegal drugs along with their catches. They waited in the shadows, ready to look for the evidence that would confirm the rumors.

Out on the dark waters, a 42-foot scallop-dragger named Joshua’s Delight glided toward the harbor. One of the fishermen aboard that night was my father, Frank Ryan, then 33. He shared a two-room cottage with my mother and me, then just a toddler. Our drafty cottage was built for two seasons, but we lived there all year long—it lacked indoor plumbing and was heated with a wood stove. Despite fishing these waters for almost ten years, he was barely able to keep our small family fed.

That night, he hoped his luck was changing. Joshua’s Delight’s 300-horsepower engine strained under the weight of the day’s catch—over a thousand pounds of scallops. The haul was worth $7,000, about the cost of a new pickup.

My father wasn’t thinking about scallops, though. While dredging the ocean floor that afternoon, his nets had caught something else. When he and the crew hauled them up, among thousands of scallops were chunks of a sticky, leathery substance shaped like the sole of a shoe. Dense and potent, you could smell it the instant it came on deck. Hashish.

My dad and the crew exchanged nervous looks, but they were excited, too. They’d heard about the hashish — a resin derived from the cannabis plant, more potent than marijuana —lying on the ocean floor from other fishermen who’d inadvertently hauled it up in seasons past. There had been vague stories of it being dumped overboard by drug runners. “Maybe it was connected to the mafia, I don’t know,” he told me. “During Prohibition, there were rumrunners. Maine has always been a good place for smugglers and pirates.” Back in the early 1980s, he continued, scallop nets pulled up so much that many fishing vessels carried a five-gallon bucket to stash the contraband.

After all the stories, my dad and the crew were finally getting a piece of the action. Over just a few years, an entire drug economy had sprouted up around the mysterious bounty. “Everybody knew somebody who smoked pot,” my father told me. “Once the word got out, everybody would ask the fishermen if they had some of that hash.” That day, they pulled the sticky resin out of their lines in pieces, he guessed about 20 pounds. It would be worth about $8,000 on the local market. If he brought it to Massachusetts, it would go for even more.

My dad tried to keep calm as he helped the crew tie up the boat. He reassured himself that there had been very little surveillance of fishermen. In those days, the industry had no quotas and few regulations. The small coastal fishing towns were also buttoned up. If a few fishermen were selling hash they’d stumbled upon, folks generally kept it to themselves. That was the Maine way.

My father began unloading when he spotted the lawmen approaching the boat ramp with their dog. He quickly stuffed the hash into a white plastic scallop bag, then tossed it to the captain, who popped a hole in the bag so it wouldn’t float and dropped it over the stern. The cold, inky water swallowed it quickly.

As the lawmen boarded, the four fishermen froze. They hadn’t had time to wash the deck. The powerful scent of hashish lingered on the fish totes.

The dog began sticking his nose in everywhere, barking and wagging his tail. My dad knew there were still small chunks and pieces of hash in the bucket he’d dumped into the scallop bag. He anxiously shifted from one foot to the other, watching the dog skitter around the boat in a frenzy.

The lawmen examined everything on deck, opened up all the bins, then went down into the forecastle where the crew of four cooked, ate, and slept. After thoroughly searching the vessel, they found nothing incriminating. As my father tells the story, they reluctantly left to meet another fishing vessel pulling into port.

Perley Fogg was at the helm of the Surf King. Short and stocky, the 27-year-old was one of the most successful fishermen in the region but had a reputation as an unrepentant scofflaw. One year, just before the season officially opened, he surreptitiously went scalloping four nights in a row. He told me he hauled up $28,000 worth before his competitors even had a shot at the action.

On this day, Fogg recalled, he had collected some 50 pounds of hashish. But someone had warned him about the authorities. Perley, he’d announced over the radio, if you’ve got any small scallops, you better get rid of it. On the way into Northeast Harbor, Fogg had hauled up someone else’s lobster trap and stuffed all his hash into it, then dropped it near Hunters Beach. He’d leave it there for a few days while things cooled off.

The minute Fogg tied up, the authorities boarded his boat with their dog. But he was a smart aleck. Before the animal could get a good sniff, he said he throttled his vessel’s big Cat diesel engine. It roared, sending up huge plumes of exhaust and sea spray, rocking the boat hard.

Startled, the dog jumped overboard, splashing into the near-freezing sea water. His handlers scrambled to pull him out. “Shut your engine off,” an officer barked at Fogg.

“What d’ya say?” Fogg cackled, leaning against the throttle. “Rev the engine up?”

“Shut it off!”

Fogg just swore at them and revved his Cat engine higher.

As they pulled their dog out of the icy water, Fogg could be heard hollering, “The Cat scared the dog! The Cat scared the dog!”

It took my father 26 years to tell me about his hashish fishing days.

It was 2009, and I was living in Boston, getting a graduate degree in mental health counseling and thrilled to finally be escaping the hand-to-mouth way of my childhood. In middle school, TV taught me about the world outside, and a sense of shame settled in as I realized how little we had compared to what I saw on screen. I fantasized about being middle class, driving a new car, living in a house that didn’t look like it was falling apart. I yearned to live in a city and work as a professional at a desk, something neither of my parents had ever done or wanted to do.

Each summer while earning my degree, I returned to Mount Desert Island to work at an art gallery that sold paintings to wealthy summer people. Among the who’s who of “cottage” owners on the island were the Rockefellers, the Astors, the Johnson family of Fidelity Investments, and Martha Stewart. At work, I hung paintings, tracked inventory, and served wine and cheese at openings. During that time, I became all too familiar with the “haves” of the island. Some were polite and friendly, but many looked right past me as I served them. In spite of myself, I mostly admired them.

Some nights after work, I’d sit with my father at his kitchen table while he nursed a Budweiser, recounting tales of his fishing days. He’d worked on boats from the mid-1970s to the mid-90s. Between fishing seasons, he did carpentry, which he eventually took to full-time when the bottom fell out of the fishing industry.

One day, my dad told me a tale about fishing for sunken hashish. At first, I didn’t believe him. Why would there be drugs at the bottom of the sea? He knew few details about how the hash had found its way there, other than it had apparently been scuttled by drug smugglers, so I listened with some skepticism. But every time my father told his hash story, his face would light up.

Soon, it became my summer ritual to head back home to Maine and hear more of my father’s stories, and I started recording them on my phone. He suggested I talk to the other fishermen who dragged up the hash, and I began to think of collecting their stories. I felt there was value in preserving a piece of a moment in rural Maine life before it was forgotten.

In 2011, I began reaching out to more than 20 fishermen I’d known as a kid. A dozen finally agreed to tell their stories of fishing for hash, though few agreed to use their names out of concern for their connection with any illegal activity. They spoke about towing the stuff up in their nets, how you could immediately smell it on deck—a potent smell, like clam flats.

Fishermen would take the chunks of hash home, scrape off the viscous sea slime, and leave it to dry. For a time, it seemed like it was everywhere: “You'd be walking into someone's house and you say, ‘What the hell is that smell? Is your septic tank backed up?’” Oscar Look, a lobsterman from South Addison, told me. They’d say, “‘No, no, no, we're drying some of that sea hash.’” (Look died in 2014.)

As the fishermen tell it, some cast the hashish back to sea, for fear of getting into trouble with the authorities. Some smoked it. Some sold it locally; some took it to Massachusetts, New York, or Philadelphia where profits were higher. They told me about hiding it in lobster traps, then using large plastic buckets and duffle bags to transport it.

According to them, between 1980 and 1984, hash money was everywhere. One man bought a new pick-up truck. One bought a new boat. One, legend has it, bought an entire house in Bar Harbor. My father called the whole thing “the Downeast get-rich-quick scheme.”

It didn’t always go according to plan. One fisherman told me that he and a friend had driven a trunkful of the stuff over the border to Canada to sell it at a biker bar, apparently at the urging of a contact they’d made. They left the drugs locked in the car and went in for a drink. “When we came out,” he says, “every door in [our] vehicle and the trunk was all busted open and everything was gone.” They’d been set up by the buyers. “We were young and dumb. All we got out of it was a buzz.”

No one really got rich, though. Most fishermen considered the sea-hash a nice little bonus, a gift from the sea. But it didn’t matter: once word got out, boats from New Bedford to Texas showed up to get a piece of the great “sea hash” gold rush. “There were boats where they wouldn’t get one scallop and they’d be towing on the hash,” recalls Mike Berzinis, former captain of a boat called the Miss Emily. “They’d sift the sand like gold miners. They were obsessed with it.”

One thing I couldn’t figure out was how the hash had found its way to the waters of rural Maine in the first place.

One fisherman had mentioned a boat called the “Tusca,” and when I brought it up to others, their faces lit up. I began getting bits and pieces of what was obviously a much larger story. I spent days searching newspaper archives for a boat with that name, to no avail.

Then it dawned on me: that Maine accent. What I was looking for was not the Tusca, but the Tusker. That was the 137-foot seagoing tug that showed up in Little Machias Bay on the frigid evening of December 11, 1978, carrying tons of hash.

The Tusker had been owned by the Coronado Company, a drug trafficking organization founded by high-school friends in the late 1960s in Coronado, California, close to the Mexican border. At first, Coronado’s founder, Lance Weber, who was featured in a 60 Minutes piece on the “Coronado Mob,” would swim in a wetsuit and flippers up the coast from Mexico with plastic bags packed with around 20 pounds of pot attached by a tether to his belt. As they they earned more money, they recruited more smugglers and purchased boats to transport their haul.

In 2015, I tracked down Lee Strimpel, a former Coronado operative, through a retired DEA agent. Shortly after talking with me on the phone, Strimpel invited me to meet him in-person in Texas, where he lived in a camper on a friend’s ranch with his wife, a painter. Struggling to reinvent himself after his eventual felony conviction, Strimpel had moved to Texas to become a ranch manager.

The day I visited him, Strimpel was in his late 60s, a tall, thin, affable man wearing the obligatory cowboy hat and boots. He told me that he joined the Coronado Company in 1973. He had gone to high school with other members, including his close friend Dave Vaughn and Lance Weber. The operation expanded quickly when their Spanish teacher, Lou Villar, joined to help communicate with their suppliers. Over the next decade, they reportedly smuggled more than $100 million millions of dollars’ worth of marijuana and hash into the U.S.

By 1976, the action on the West Coast was getting too hot. After a DEA indictment, they decided to relocate the entire operation to the East Coast. With its countless harbors, bays, inlets, and outlets, plus remote woods sparsely populated by people known for keeping to themselves, the Maine coast seemed like the perfect place to run a smuggling operation. In just three years, between 1977 and 1980, more than a dozen such operations would be busted along its 3,500-mile shoreline, according to TKSOURCE.

As Strimpel tells the story, the Coronado Company needed a base of operations. On a dead-end road in Cutler, Maine, they found an old farmhouse, complete with a barn and a beautiful ocean view out to the Black Ledges, a series of shoals and precisely the landmark they needed to locate the house from sea. Strimpel recalls Vaughn asking him to join them: the pair posed as rich businessmen. Before sealing the deal, they flew in a small plane over the property and coastline so they could see it from the air. It looked perfect.

For a caretaker and contact, Strimpel installed his long-time friend, a carpenter named Roland (“Ron”) Weber and his wife in the house in Cutler. The couple’s job was to keep a detailed daily log of any sightings of air, vehicle, or marine traffic. They were also expected to ingratiate themselves to the neighbors, have them over for dinner, then send back reports on anything they picked up.

In May of 1977, according to Strimpel, Coronado successfully smuggled tons of Moroccan hash through Maine. A second smuggling operation that October brought in tons more of Thai stick, which were marijuana buds wrapped around a piece of wood and tied with leaves. The operation was dangerous but lucrative, in Strimpel’s telling. “I would say we paid [our supplier] between $100,000 to $150,000 a ton for Thai stick,” he explains. “It cost us half a million dollars per ton to get it on to the beach. This stuff would roughly go for $300 to $500 an ounce on the street. Ultimately, it was worth $150 million, all told.”

High reward, but also high risk. And they were pressing their luck.

In November 1977, the Tusker set out for the third operation, departing from Pakistan with TONS? Of Afghani hashish worth millions of dollars. The Tusker motored for some 50 days, going all the way around Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. (“You just don’t drive up to the Panama Canal with [that much] hash and slip through,” Strimpel says.)

During a storm in the North Atlantic, the crew failed to take down the antennas, which then froze and broke off. Later, the vessel lost heat. By the time the Tusker reached Maine, the crew was hypothermic.

Strimpel worried that he’d had no communication with the Tusker since the vessel left Pakistan, but he knew when they were expected to arrive. He also knew the house in Cutler was getting too hot. Weber had reported seeing a red Chevy Blazer repeatedly drive by the house; he’d seen the same vehicle often parked at the police station.

Strimpel devised a new plan. On the evening of December 12, two days before the Tusker was due to arrive, he set out from shore in a Zodiac inflatable boat. He’d started 10 miles south of the Cutler house, an effort to make sure he wasn’t being trailed. He planned to beach the boat, break it down, and lug all the equipment through the back of the Cutler house, then start working the radio to make contact with the Tusker.

As Strimpel motored up the coast that frigid night, feeling his way for the Black Ledges, his heart practically stopped when saw something looming large in the moonlight. It was the Tusker. “She was sitting right there,” he recalls. “This huge boat, 137-feet long, 35-foot beam, 30-foot draft, 390 tons. This thing was bigger than big. Full moon, and there was this ship sitting there. And I was going, “[Expletive] me.”

Strimpel hadn’t planned for this. He picked up Weber and motored straight to the ship. “You need to get outta here right now,” he told the captain, “And come back into a different place in five days at 0900.” The captain told Strimpel that he’d already sent two crew members ashore.

With horror, Strimpel realized that the Tusker had been sitting out there for two days, in full view of shore. He and Weber tried not to panic. They turned the Zodiac back toward shore. Before they landed, a Coast Guard cutter appeared with lights blazing, heading straight for the Tusker. They’d been spotted. “I look up on the cliff overlooking the water and saw 20 or 30 guys, and I could hear them saying, ‘There they are! We got ‘em!’” he recalls. “The only thing I could do…was make a run for it.”

Strimpel knew he wasn’t going to outrun the Coast Guard in the Zodiac. He motored past the Cutler house toward the trees, beached it, and pulled the drain plugs. He shoved the Zodiac back out in the water where he hoped it would sink before the authorities discovered it. Then he and Weber took to the snowy woods.

Strimpel knew the area intimately—he’d hiked it to prepare for this exact scenario. “I was ready to rock and roll. I had full packs. I had topographical maps of the area. All we had to do was hike a few miles through the woods back to the main road.”

Strimpel knew that the lawmen wouldn’t recognize them as connected with the Coronado Company. “I wouldn’t care if they found me on that highway,” he said. “We would’ve been five miles away from the scene and would’ve lost the maps and anything else that tied us to the bust.”

A few hundred yards in, they decided to hunker down into their sleeping bags amid the trees to wait. Dawn would come in a few hours. They could head for the road then.

But Strimpel had made a mistake: He’d forgotten to pull the keel plug of the Zodiac, and the boat was still floating just offshore when the Coast Guard and other authorities arrived. They fanned out to track the men, following the deer trails and footprints in the snow.

Around 3:30 in the morning, Strimpel awakened to the sound of men approaching and knew the game was over.

He served two years in federal prison and five years on probation.

How did the Coast Guard know to look out for the Tusker? Blame the very thing they thought would protect them: insular Maine. A neighbor living up the street from the Cutler house happened to be a Maine Marine Patrol officer named Leigh McKeen who got suspicious of the hive of activity around the house. McKeen tipped off the authorities and in the month leading up to the December drop, the Cutler house was under surveillance.

When the Coast Guard heard from locals wondering why a very large vessel appeared in Little Machias Bay on December 11, they hoped this was the drop they’d been waiting for.

The Coast Guard sent out two boats at different times to intercept the drugs. When the first cutter crew boarded the Tusker, they found nothing, so they led the boat back to port for further questioning. “[I]t was a pretty big boat to look over in a few minutes and they had no idea what to look for,” recalls Garry Moores, a US Coast Guard officer who was on duty during the bust. He surmises that the officers were looking for bales of marijuana, but the hash was packed “like pancakes” in metal canisters.

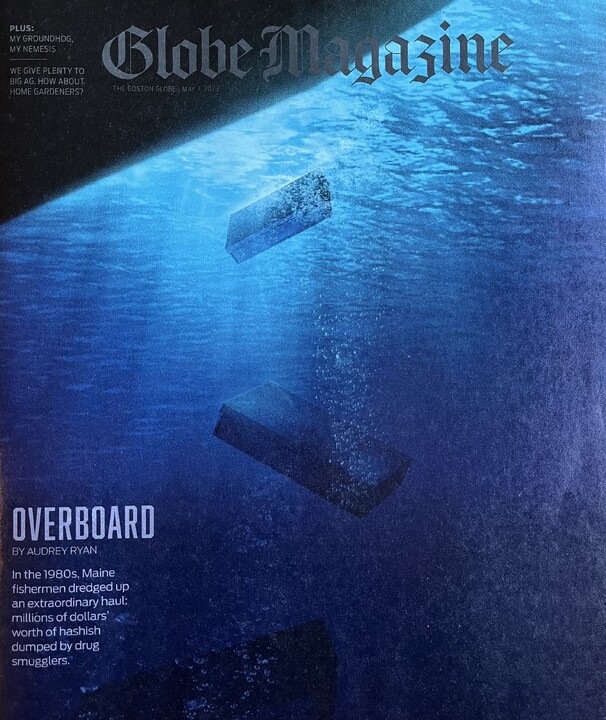

Strimpel remembers the canisters as about two feet long, a foot wide, and 7 inches deep. Each one weighed about 75 pounds. During the Tusker’s short journey to shore, the crew managed to throw many of the canisters overboard. Later, locals talked about hearing the splashes. Many, many splashes.

Fishermen started finding the canisters at sunrise the very next day, Moores remembers. A few were floating; others had broken open underwater. Over about a week, state divers reportedly recovered between 500 and 600 pounds of hash from the ocean floor–at one point, they estimated what they’d found had a street value of $1 million. But they didn’t find it at all. “We had enough evidence to prosecute them,” Moores says.

Strimpel says that even while he was sitting in jail awaiting arraignment, he pictured all the sunken canisters of hash left behind in Little Machias Bay. “I thought of the scallopers,” he says. “I knew they were going to have a heyday. ‘Here’s a gift, boys.’”

The gifts of from the sea continued for some time. In 1983, five years after the operation in Little Machias Bay, authorities in Maine seized 108 pounds of hashish–with a street value of more than $100,000–and arrested three local men. The drugs were believed to have originated from the canisters the Tusker crew tossed overboard. “This has been an on-going problem from individuals in the coastal area of eastern Maine,” the head of the Maine State Police Organized Crime-Drug Unit said at the time. Subsequent raids reportedly uncovered more drugs, plus 16 firearms.

Former Special Agent Michael Cunniff, who was among the law enforcement officials who caught Strimpel in the woods, speculates that for every successful bust during Maine’s drug smuggling era, there were likely ten operations that proved successful. “There were all kinds of deals going on and I knew people all over New England doing crazy stuff,” says fisherman Mike Berzinis. “Some of the names are still floating around, like Whitey Bulger and all those guys. He used fishing boats to smuggle guns to the Irish Republican Army, all this crazy stuff.”

Other fishermen, like my father, were dabbling at a far smaller scale, often trying to make a few bucks or just feed their families. Cunniff takes care to emphasize that the DEA was sensitive to the fact that the fishing industry was getting tougher. “Our focus, the task force of federal and state authorities, was on organized crime,” he says. “We were not trying to chase down fishermen, who were sort of victims of economic circumstances, who were being used by organized crime groups. Those folks were desperate to pay their bills, and gangsters exploited them. It was kind of a human chess game.”

Cunniff says that the DEA and the DA made a clear distinction between “criminals” and “outlaws.” Criminals were repeat offenders who often turned to violence and lacked empathy for people that stood in their way. Outlaws were people like my father and Perley Fogg. They lived seemingly regular lives—family men—but, as Maine fishermen, perhaps perpetually wary of the government and authority figures. The criminals were pursued in earnest; the outlaws apparently weren’t.

In the forty years since my father’s encounter with the authorities in the harbor, both the fishing industry and Mount Desert Island have become practically unrecognizable. Fishermen have weathered decades of increasing regulations and fishing quotas. Ground fish are all but gone and fishing licenses are scarce. The lobster industry, the only part of fishing that has remained relatively stable in recent years, is now facing a battle with ocean conservationists who believe their traps are disrupting the ecosystems of endangered species.

Meanwhile, Mount Desert Island and the areas around it are huge tourist destinations. Most of us who grew up there, my family included, have seemingly moved off the island to the mainland, where there was still a semblance of the Maine we grew up in--including less traffic and property about half the price.

Almost all the fishermen I interviewed who fished in the 70s and 80s have long since left the industry. They have pivoted to various other jobs – security guards, welders, truck drivers. Perley Fogg still holds a fishing license but mainly makes his living selling bait to lobstermen. My father left fishing in the 90s for carpentry, and has been a builder in Maine ever since.

I still remember glimpses of his fishing days during my childhood; the nights he brought home fresh caught fish, snails as big as baseballs, and lobster too big to sell. In one Polaroid picture, an oversized lobster is holding a loafer in his giant claw. Now I’m older than my father was back then, raising my own kids in the outskirts of Boston in a community of what us “have nots” used to call the “haves.”

As for the drugs, recreational marijuana was legalized in Maine in 2016, with close to a hundred dispensaries popping up around the state and about a dozen within an hour of Mount Desert Island. In 2020, cannabis became Maine’s most valuable crop, outpacing sales of potatoes and blueberries. It’s hard to envision that half a lifetime ago, the area was awash in smuggled drugs pulled from the bottom of the sea. Today, my father, like many others, grows weed legally in his backyard.

Audrey Ryan is a psychologist originally from Mount Desert Island. She lives in Newton with her husband and two children. Send comments to magazine@globe.com.

Creative Operations, Strategy, Creative/Art Direction | Dir. Creative Ops @ Laetro

11moThis ruuuuuuuuules Audrey.

Building a healthy and sustainable future for us all.

11moGreat read!