Frank Gehry is both architect and artist. His mastery of design, and technology — combined with the intricacies of planning and plumbing, clients and materials — make him a modern Leonardo. He has created a portfolio of distinctive buildings — some metallic and curved, others composed of street materials, but all built with a respect for utility, emotion, freedom and on a grand, but fixed, budget.

At 88, he shows no signs of slowing down — several new Gehry buildings open around the world every year. He sat down in his Playa del Rey studio, littered with models for Gehry buildings past and future, for a conversation about his career, his buildings and his methods. This transcript has been condensed and edited for clarity.

WILL HEARST: When you were a kid, what attracted you to architecture? What made it interesting?

FRANK GEHRY: Well, I wasn’t interested when I was a kid. I was interested in jazz, and I was interested in physics, science, chemistry. Some literary stuff interested me. I was interested in flying. I was very interested in politics, I was very interested in religion and finding out that I wasn’t religious, finding out that I didn’t believe any of that.

I used to go to the architecture lectures at University of Toronto on Friday nights. My friends would never go because they were always out playing and dating, and stuff like that. It was something that held my interest, and I kept going, I kept going alone, and one night a gentleman who turned out to be [Finnish architect] Alvar Aalto gave a talk, and I never forgot that talk. I didn’t know Aalto. I didn’t know much about architecture.

HEARST: When did you decide to pursue architecture as a career?

GEHRY: In high school, we had these vocational guidance books of different professions, and I remember looking at architecture. And the exam at the University of Toronto for graduating in architecture was to design a little stone village kind of house. Very romantic. I read all those things, and I said, “Shit, I’m not interested in that.” I was more interested in making things. I took shop and I made things, but I wasn’t interested in copying drawings.

PRE-POST-MODERNISM

Gehry started out as a fairly conventional architect of homes and commercial buildings. But he began to break away from traditional architectural forms in the mid-1970s, frustrated by the strictures of traditional design and increasingly fascinated by unusual materials and techniques, and what was becoming known as post-Modernism. His new direction had its origins in a landmark exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) that delved deeply into Beaux-Arts, the European neoclassical style that relies heavily on elaborate sculptural decoration.

GEHRY: This was right when Modernism was hitting its dead end. And everybody was looking for the new way, right? Modernism was cold — it was mechanical. It wasn’t that the architects that made it were mechanical; it was the way it was subverted by the culture.

There was a sigh of relief when the MoMA show happened because all of a sudden you saw these beautiful renderings of Beaux-Arts buildings. And they were very seductive. Everybody just went gaga over them. And so, all of a sudden, there was a turn. Philip Johnson did [New York’s AT&T building], Charlie Moore, Michael Graves. I think everybody was looking for a humanistic gesture that would soften the blow of Modernism. I got pissed off because I grew up a Modernist, right, in those years, and I was committed.

THE SANTA MONICA HOUSE

One of Gehry’s most notable buildings in his evolution to post-Modernism was his own home, in Santa Monica — a riot of corrugated metal, chain link and other unusual materials.

HEARST: I see your Santa Monica house as perhaps the first time that people thought, “Who is this guy? What is he doing? This is something. Is he different, is he too different, what’s going on? I have to pay attention to that.”

You’ve changed the way we look at the world. When I first went to your house, I thought, “He’s got all this plywood and chain link.” But there was a wonderful spirit in your kitchen. Inside this crazy box with the wild windows, it felt like I could spend all day in this kitchen.

The other thing was, in my brain, I heard your voice saying, “Walk out there onto Pico [Boulevard, in Santa Monica] and have a look. What are you doing to see? Do you think you’re going to see the Taj Mahal? You’re gonna see chain link, you’re gonna see plywood, you’re gonna see a construction site with scaffolding. That’s the actual city.”

GEHRY: Well, the chain link was really about that. The chain link was — I get fastened on an idea and then I’ve got to act on it. I went to a lecture on denialism with a bunch of shrinks and the mechanism and what it means in the culture and everything. And I was trying to find the expression of it in architecture. I found it.

Chain-link fence is the most produced product in the world. And it’s absorbed by every culture in the world. And it’s the most hated material in the world. So that is the essence of denialism. I thought: “Here’s a great model. Here’s something to really explore. How can you take the essence of denialism and flip it?” And that’s what I was trying to do.

HEARST: How did you start to develop your post-Modernist style?

GEHRY: I think everybody was looking for a way out of Modernism, and they were trapped. Then came the MoMA Beaux-Arts show. Everybody was seduced by the beauty of it. This was buildings with all kinds of decoration — cornices and vaults and stuff like that. It’s quite beautiful. It’s very seductive. If you were Michael Graves and if you were Philip Johnson and if you were the young architects sitting there, [you were] trying to think of what the fuck do we do next. And all of a sudden MoMA shows you what somebody did, what a whole culture did for a number of years. And we had ignored it. It’s not copying Greek temples. It’s much more rich and refined and open. It’s an open system. You can take it anywhere.

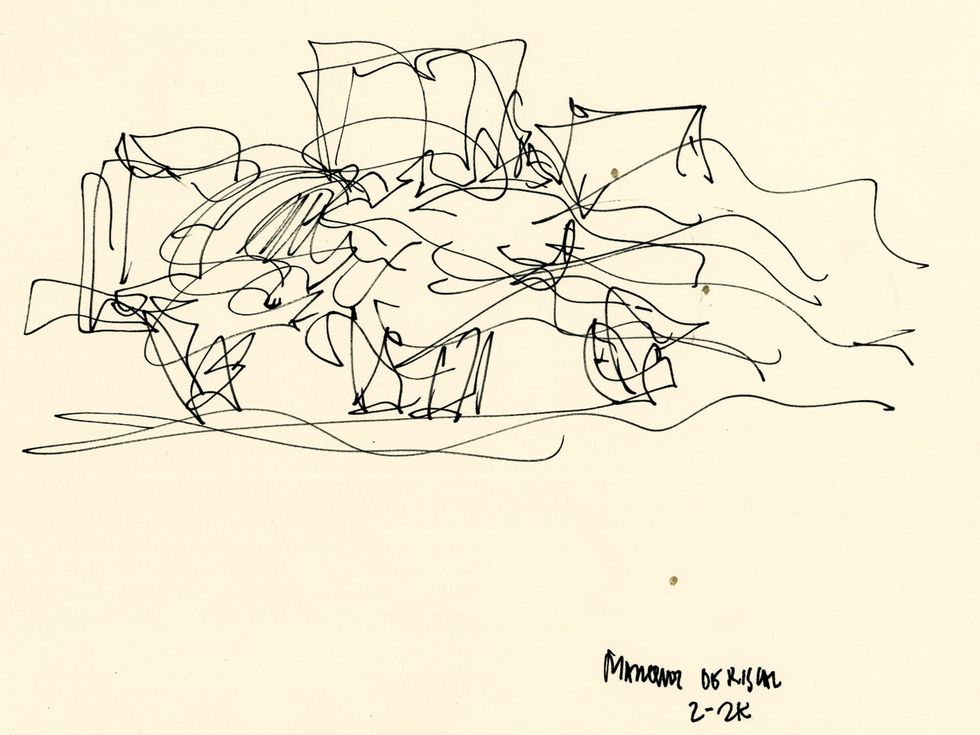

I was looking for movement. Because I said that the culture is living in a state of movement. Everything around us is moving. Planes, cranes, cars. So, I was looking for a movement of vocabulary to replace Modernism. But how do you build this? I had to invent all the technology.

BILBAO AND SUPERSTARDOM

While Gehry built an impressive portfolio in the early years of his career, he vaulted onto the architectural Olympus with the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which opened in 1997. Its swooping, shiny titanium exterior made the building an immediate sensation. Gehry’s friend Philip Johnson declared it “the greatest building of our time.” The Guggenheim Bilbao defined Gehry’s version of post-Modernism and made him a star among architects — what some commentators called a “starchitect,” a term Gehry loathes. Bilbao led to a series of dramatic Gehry buildings made possible with modern materials and computer-aided design. And it put Bilbao on the world map.

GEHRY: Bilbao had a powerful director, Tom Krens, who had a mission. He wanted to do something, he wanted to achieve something. We had the Basque government, which was in the doldrums because financially they were in really bad shape. The shipping business and the steel business are failing. Kids that lived there, high school, they left. So, they were migrating out, the families were losing. It was in the hole.

HEARST: Did you get into all that discussion in the form of research?

GEHRY: Well, you could see a lot of it, but I did spend time meeting with the minister of culture, the minister of commerce, the mayor, the president.

HEARST: Before you started to draw anything?

GEHRY: Yes, yes, I met with all of them. I had done a sketch model. The model had a lot of the feel, a lot of the important features. The main thing was, it had to relate to the old city, it had to relate to the river, it had to relate to the center of the city.

HEARST: For me, Bilbao changed the meaning of the word context. The first image I remember of it is looking down this dark urban street, with the laundry out on the balconies — and then there’s this gleaming building that is the most anticontextual thing, like a spaceship has landed by accident in Bilbao.

GEHRY: But if you go there now, you’ll see it’s contextual.

HEARST: To me, the brilliancy of it was that you changed the meaning of context. It’s not a little copy of the street leading up to it. And it works so well. It’s rebranded a region.

GEHRY: Plus, the separatists laid down their arms, they tell me, because they have now an identity.

HEARST: What was your design process for the Disney Concert Hall?

GEHRY: Well, a theater starts with Shakespeare. All the world’s a stage. The world is a stage. Wherever we sit, it’s a stage. In doing a theater for the performing arts of any kind, the relationship between audience and performer is critical. It’s not thought about a lot, but one of the most central issues is the audience response while they’re sitting passively in a theater, the experience of the orchestra and of the performers. You feel it yourself when you’re giving a lecture. When you’re giving a lecture in the wrong auditorium, you know it. So that’s the issue. And you can design that. You can be careful about that.

If you go to Disney Hall for a concert and talk to the people, they’ll tell you they really have a great feeling being there, of community and participation, even though they’re sitting in a seat.

HEARST: The acoustics are supposed to be very good.

GEHRY: Well, the acoustics, yeah, but you can have a room full of great acoustics and not have the humanity.

HEARST: How do you think about the interior part of a building? For a museum, or a department store, they don’t want windows because it’s a box to hold things, but for a lot of other buildings, the interior is the place where people live and work. It seems like your sketches are usually of the exterior. What’s your interior model?

GEHRY: Well, I think I’m more open-ended about that than a lot of architects. The model for Frank Lloyd Wright and the European architects, the Wiener Werkstätte and all that stuff, was to design everything. The architect designed the space and designed everything.

I’m not that dictatorial. I like the idea of watching how people interact with the space and what they bring to it on their own. If it’s a residence — certainly a comfortable environment that they feel is kind of like an old shoe, where they feel like they can relax and stuff — it’s got to be like that. In a Frank Lloyd Wright house, I don’t think you can feel exactly like that. I’ve stayed in a Frank Lloyd Wright house, and you’re aware of him at every detail.

There’s a certain over-design in luxury houses, doing the cabinets special with the marble top, and the decorator goes and finds the right marble. That’s too fussy for me. I like a more casual thing. And since I don’t do a lot of rich-guy houses, I don’t run into the other problem.

HEARST: People know that you always had a big interest in art, and you have friends who are artists. In Barbara Isenberg’s book (“Conversations with Frank Gehry”), you discuss the difference between art and architecture. As I recollect it, you said something like, “Well, a great work of art doesn’t have to have a bathroom.”

GEHRY: Well, I was cavalier about it. And the fact is that the only reason I say things like that is I didn’t want to get into a discussion about it because it’s a big issue with artists.

HEARST: Artists resent you being thought of as an artist?

GEHRY: Oh boy, yes. Some of them do.

ART VS. ARCHITECTURE

This clash between art and architecture has been exemplified by a notorious quote from American sculptor Richard Serra who, like Gehry, works in curvaceous metal forms — but sees architecture as an entirely different discipline: “I don’t think there is any possibility for architecture to be a work of art,” Serra was quoted as saying in Francesco Dal Co’s “The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Iconoclastic Masterpiece.” “I’ve always thought that art was nonfunctional and useless. Architecture serves needs which are specifically functional and useful. Therefore, architecture as a work of art is a contradiction in terms.”

GEHRY: Architects don’t realize they are artists; that they all really come from a lineage of artists. The great architects of the past were artists: Gioto, El Greco, Michelangelo, Bernini, you name ’em. And they were recognized; in fact, the stepping from painting to being an architect was a step up in those years. And they still had to figure the plumbing and all the things, not to the extent we have.

HEARST: I never get the sense that you labor over these formal restrictions of planning commissions and bathrooms and the janitors’ closets.

GEHRY: Well, I work ’em out.

HEARST: You impress me as an opinionated person, but not a troubled person.

GEHRY: I’m not into the prima donna stuff at all. I don’t like that, for me personally.

HEARST: What did a journalist say that made you shoot them a finger (in a famous incident in 2014)?

GEHRY: Well, I went to Spain to receive the Prince of Asturias award [from] the new king. We were really tired, and we were told that the press conference that we had originally scheduled was not going to happen. So I got to the hotel room, I got undressed, took a shower, climbed in bed, started reading the paper. Two hours later, I get a call. The press conference is on, and they’re waiting for me.

So I got dressed and went down. I was feeling kind of cranky. I told them I was feeling cranky. I got the question: “When people say your work is showy, what do you say?”

I sat there like Dr. Strangelove. And it was just, I couldn’t help it. I was thinking, “What the fuck are you talking about?” All the shitty buildings around, everything … Up it went.

The next day, I met the king and he hugged me, he thanked me. He said, “Thank you for doing that.”

But after I did it, I looked at the [journalist] and I said, “Look, most of the buildings in our countries, in all of our countries, are pretty banal. Very banal. I’d say 98 percent. Why don’t you talk about that? Because that’s a really important thing you could talk about.” He was dumbfounded. But I gave him what he needed. He got his place in the sun because he provoked the big finger.

HEARST: One of your buildings that I really admire is this little barn, the O’Neill Barn, in San Juan Capistrano. It’s open on the sides, which turns out to be a smart thing to do, so it’s never fetid or damp. And the other thing is the roof guides the rain water without gutters. It’s a minimalist jewel. As you would say: Tell me your program, tell me the feeling you want, and I’ll give you a barn! It’s a lovely little building.

GEHRY: Two thousand dollars built it.

Will Hearst is the editor and publisher of Alta Journal, which he founded in 2017. He is the board chair of Hearst, one of the nation’s largest diversified media and information companies. Hearst is a grandson of company founder William Randolph Hearst.